https://socialanxietyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/I-know-what-i-want-to-say-but.jpg

577

471

Odhran

https://socialanxietyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/sai.png

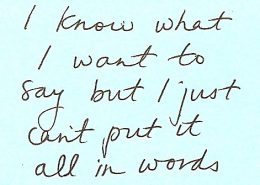

Odhran2018-09-25 15:57:552018-10-05 20:36:00What I Want To Say.

https://socialanxietyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/I-know-what-i-want-to-say-but.jpg

577

471

Odhran

https://socialanxietyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/sai.png

Odhran2018-09-25 15:57:552018-10-05 20:36:00What I Want To Say.affecting approximately 13.7% of Irish adults at any one point in time.

Menu: The Group

Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioural group therapy (CBGT) for social anxiety disorder: immediate and long-term benefits

Odhran McCarthy1, David Hevey2, Amy Brogan1 and Brendan D. Kelly3

1 Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

2 School of Psychology, University of Dublin, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland

3 Department of Adult Psychiatry, University College Dublin, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Copyright © Cambridge University Press

Correspondence

Author for correspondence: Dr O. McCarthy, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, 63 Eccles Street, Dublin 7, Ireland (email: omccarthy@mater.ie).

Abstract

This study examines the effectiveness of a group CBT (CBGT) intervention in reducing a variety of symptoms and problem areas associated with social anxiety disorder. A longitudinal cohort design assessed changes in standardized psychological scales assessing general mood and specific aspects of social anxiety. Questionnaires were completed pre-programme (time 1, n = 252), post-programme (time 2, n = 202), and at 12 months follow-up (time 3, n = 93). A consistent significant pattern was found for all variables: pre-intervention scores were significantly higher than both post-intervention scores and 12-month follow-up scores. Large effect sizes were found and rates of clinical significant changes varied, with over half of the participants recording clinically significant changes in general mood. Individual CBT can be translated successfully into a group format for social anxiety. Given the high completion rate, the intervention is acceptable to participants, feasible, and effective in a routine clinical service.

Key words: Cognitive behaviour therapy; group therapy; social anxiety;treatment outcome

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), a marked persistent fear of social or performance situations in which embarrassment may occur (APA, 2000), tends to be a chronic disorder; the duration is often life-long and co-morbidity with other psychiatric disorders is very common (de Wit et al. 1999). The National Comorbidity Survey of over 8000 Americans revealed a 12-month SAD prevalence rate of 7.9% and lifetime prevalence rate of 13.3%, making it the third most prevalent psychiatric disorder and the most common anxiety disorder (Kessler et al. 1994).

Given its prevalence and chronic course, many therapists will have a number of individuals with social anxiety on their active caseloads; such individuals may represent a substantial drain on limited resources. The current economic climate in healthcare emphasizes efficient provision of empirically validated treatments in an accessible, yet cost-effective manner. Although cognitive-behavioural interventions for individuals have been successfully developed for the treatment of social anxiety, group interventions may represent an efficient method of treatment if they can be proven to be effective in clinical practice settings.

Based on a cognitive model of social anxiety that emphasizes the role of self-focused attention and negative self-referent thinking (Heimberg et al. 1995), Heimberg developed a successful group CBT (CBGT) treatment programme, which has been widely adopted in the USA. Heimberg’s approach focuses on the identification, analysis and restructuring of negative social cognitions combined with exposure work. In the UK, Clark & Wells (1995) developed a similar conceptualization of social anxiety and their treatment model was originally formulated with an individual therapeutic format in mind. To date, research using this model has focused mainly on individual CBT sessions; however, given the limited resources available, a group-oriented CBT programme based on the Clark & Wells model may deliver empirically validated care in a cost-efficient manner.

CBGT vs. individual CBT

Research comparing individual CBT to CBGT for social anxiety has, to date, produced mixed outcomes. Stangier et al. (2003) randomly assigned participants to CBGT, individual intervention or wait-list control. Both CBGT and individual modalities received 15 weekly sessions using Clark & Wells’ (1995) treatment model. Individual CBT therapy was superior to CBGT on specific measures of social anxiety. Rodebaugh et al. (2004) reviewed five meta-analysis that specifically addressed the treatment of SAD using a CBT approach (Feske & Chambless, 1995; Chambless & Hope, 1996; Taylor, 1996; Gould et al. 1997; Fedoroff & Taylor, 2001) and noted that the meta-analyses included a range of CBT-type interventions including behavioural exposure, cognitive restructuring, social skills training and applied relaxation, which were employed in various combinations and in both group and individual formats. Rodebaugh et al. (2004) concluded that there was little evidence to suggest that either group or individual format produced better outcomes. They noted the discrepancy between their meta-analysis and Strangier et al.’s (2003) findings, and suggested that the Clark & Wells’ treatment model might be less effective in a group format. However, little research has empirically addressed this suggestion.

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme makes psychological therapies for depression and anxiety disorders widely available to address the under-provision of evidence-based treatments. CBT is a core IAPT therapeutic intervention and in a recent report (Richards & Borglin, 2011) it was noted that patients were treated in relatively few sessions (n = 5) with a short combined contact time (3 h); such an approach reflects the low-intensity nature of the stepped care system. Although positive effects were reported it is noteworthy that CBGT sessions were not provided; given the aims of IAPT, if the efficacy of CBGT can be established then such approaches provide the potential to effectively manage long-waiting lists for services.

Of particular note to clinicians, the majority of CBGT research in this area reflects efficacy studies conducted in ‘research’ environments while few studies have examined its effectiveness in real-life clinical settings. McEvoy (2007) reported that a community mental health-based CBGT treatment based on the Clark & Wells model produced outcomes comparable to those reported in the efficacy studies. Given such encouraging findings, the clinical effectiveness of such interventions warrants further investigation. In addition, few studies have addressed the issue of moderators of treatment outcome. Chambless et al. (1997) reported that initial level of depression predicted GCBT treatment gains for individuals with social anxiety; of note Scholing & Emmelkamp (1999) similarly reported a relationship, albeit weaker, between pre-treatment depression and gains from CBGT for social anxiety. Additional research identifying moderators may help inform practitioners’ treatment stratification decisions.

Aims of the current study

The current study examines the effectiveness of a community-based CBGT intervention, based on Clark & Wells’ (1995) model, in reducing symptoms and problem areas associated with SAD. It was hypothesized that the intervention would be associated with statistically significant decreases in the primary outcomes (specific aspects of social anxiety) and the secondary outcomes (general anxiety and depression). In addition, a broad range of potential socio-demographic (e.g. age, gender) and psychological moderators (depression) of treatment effects on the primary outcomes were examined.

Method

Participants

Participants were referred to the treatment programme via two routes: (1) from one of the three mental health teams operating within the study hospital itself, or (2) via a self-referral route. The majority (70%) of participants were self-referrals, who had heard about the programme through word of mouth, the Internet, the service’s own website, or from other mental health professionals. Self-referred participants were accepted if they resided anywhere within the Republic of Ireland; most came from urban areas. Participants were selected on the basis of meeting diagnostic criteria for social anxiety disorder (DSM-IV), which was established during a structured screening interview conducted by the senior psychologist in the team (O.McC.). These interviews also helped gauge and facilitate client motivation, and addressed concerns about engaging in group work. Exclusion criteria included psychotic illness, current active addiction problems, active symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, social evaluative concerns related to medical illness (e.g. acne) or mental illness (e.g. having a diagnosis of schizophrenia), autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and schizoid, schizotypal and borderline personality disorders.

Social anxiety programme

The programme was held on a weekly basis over 14 consecutive weeks within a treatment clinic and each session lasted approximately 2.5 hours; each group comprised nine participants. While recent NICE draft guidelines (2012) on SAD favour individual cognitive therapy based on Clark & Wells’ model, we maintained a group format due to significant demand for places. CBT interventions based on the model were provided. Early sessions focused on psychoeducation about the nature of social anxiety and treatment rationale. Subsequently, participants worked on the development of individual formulations based on the Clark & Wells’ model. Goal-setting was then introduced along with the principles of behavioural experiments and graded exposure. Participants were then introduced to thought monitoring and challenging. Positive data logs were subsequently included to challenge attentional biases. The identification of and gradual reduction in safety behaviours was then addressed. Later sessions focused on in-session video experiments to challenge social self-image. Video experiments were done on an individual basis in-session, with both the facilitators and other participants providing feedback. Participants identified their own role play and engaged in it both with and without their safety behaviour in place. Self-focused attention during social interactions was highlighted and attentional control skills to facilitate the development of an external focus during social encounters were practised. Other areas addressed during the latter part of the programme included: pre-event and post-event management, the quality of self-talk, social assertiveness and the development of a recovery plan. All groups were facilitated by the same senior clinical psychologist (O.McC.), while psychologists in clinical training (doctoral level) provided co-facilitation. The core Clark & Wells model was maintained over time; however, minor elements of the programme were changed based on participant feedback, e.g. participants pairing up to monitor homework

Procedure

Over an 11-year period (1998–2009) data were collected before the start of the programme (time 1), after participation in the programme (time 2) and at 12 months follow-up (time 3). Psychological measures were administered at each time point. Demographic details of age, gender and socioeconomic status (SES) were also collected.

Measures

Primary outcome measures

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clark, 1998)

The SIAS is a 20-item questionnaire that assesses anxiety relating to social interaction in dyads and groups. A high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.93) was reported in an early study (Mattick & Clark, 1998) and a similarly high level was found in the present study (Cronbach’s α = 0.85). The scale discriminates SAD sufferers from screened community volunteers (Heimberg et al. 1992) and from individuals with other anxiety disorders (Brown et al. 1997).

Social Phobia Scale (SPS; Mattick & Clark, 1998)

The SPS – often perceived as a companion to the SIAS – is a 20-item questionnaire, which assesses anxiety when anticipating being observed or actually being observed by other people and when undertaking certain activities in the presence of others. Similar to the SIAS, acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) was reported by the scale’s authors (Mattick & Clark, 1998); a high level of reliability was found in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.88). The scale discriminates SAD sufferers from screened community volunteers (Heimberg et al. 1992) and from individuals with other anxiety disorders (Brown et al. 1997).

Fear of Negative Evaluation Questionnaire – Revised (FNE-R; Ehlers & Clark, 1998)

The FNE-R is a 39-item questionnaire that provides a measure of fear of negative evaluations by others, expectation of negative evaluation, and the avoidance of evaluative situations. The FNE-R has an acceptable internal reliability (e.g. Faytout et al. 2007) and in the present study Cronbach’s α = 0.93.

Safety Behaviours Questionnaire (SBQ; Clark et al. 1995 )

The SBQ is a 28-item inventory assessing a range of typical safety behaviours used by individuals to conceal their anxiety from others, e.g. ‘avoids eye contact’. Higher scores reflect a greater reliance on safety behaviours during social encounters. Cronbach’s α = 0.80 in the present study.

Social Cognitions Questionnaire (SCQ; Wells et al. 1993)

The SCQ is a 22-item inventory that evaluates both the frequency and intensity of cognitions typically associated with social anxiety, e.g. ‘I am going red’. High scores reflect higher frequency and intensity of cognitions. Responses are averaged to produce an overall frequency score (Cronbach’s α = 0.90 in the present data) and an overall intensity score (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al. 1988)

The BAI is a 21-item scale that measures the common symptoms of anxiety in adults. The BAI has established robust psychometric properties and Cronbach’s α = 0.90 in the current data.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-2; Beck et al. 1996)

The BDI-2 is a 21-item inventory that assesses symptoms of depression over the previous 2 weeks. The BDI-2 is supported by extensive psychometric literature (Beck et al. 1996) and in the present study Cronbach’s α = 0.90.

Satisfaction

Satisfaction/feedback questionnaires were completed at the end of every group session. The questionnaire was developed by the service for routine data collection purposes. The questions asked participants to note what they perceived to be good about the programme sessions; an overall evaluation of the group was provided at the end of the programme.

Data analysis

Repeated-measures ANOVA, with Sidak post-hoc tests, determined the significance of changes over time. Effect sizes were calculated using changes in mean scores divided by the baseline standard deviation (s.d.). In line with previous research examining moderators of treatment for social anxiety (Chambless et al. 1997; Scholing & Emmelkamp, 1999), residual change scores assessed each clinical, demographic and psychological predictor’s effect on treatment outcome at both times 2 and 3. Residual gain scores control for both initial differences between patients and for measurement error associated with the repeated use of the same scale (Steketee & Chambless, 1992). McNemar’s test determined the significance of changes in categorical variables over time.

Following Oei & Boschen (2009), those with a pre-treatment BAI score of ≥11 were examined to see if any reported a clinically significant change of 10 points. A similar criterion was used with the BDI. Based on data (in preparation) from the authors’ normative samples of 350 healthy community participants, the Reliable Change Index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1991) was estimated to determine reliable change in the other measures. Clinical significance was defined as exceeding the RCI and a greater likelihood of being in the normal distribution than being in the clinical distribution; this method is recommended when distributions are overlapping (Evans et al. 1998).

Results

Sample characteristics

The mean age of the 252 participants was 32.8 years (s.d. = 9.3, range 19–66). Additional demographic details of the sample are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic details for sample

| n (%) | |

| Gender

Male Female |

127 (50%)

125 (50%) |

| Age Category

Under 30 Over 30 |

126 (50%)

124 (50%) |

| Location

Urban Rural |

194 (78%)

56 (22%) |

| Marital Status

Single Married Separated/Divorced Other |

185 (73%)

52 (21%) 5 (2%) 10 (4%) |

| Socio-Economic Status

Managerial and professional occupations Intermediate occupations Small employers and own account workers Lower supervisory and technical occupations Semi-routine and routine occupations Unemployed Student |

64 (26%)

68 (28%) 20 (8%) 16 (7%) 28 (11%) 21 (9%) 29 (12%) |

Note:n varies between 252 and 250 due to missing data

The completion rate of those who finished the 14-week programme was 94% (N = 236). Those who dropped out (n = 16) of the programme or only completed time 1 data (n = 34) were not significantly different to completers on any demographic or psychological measure. Reasons for dropping out of the treatment programme were predominantly due to external life circumstances (e.g. changing work, immigration, death in family); however, some participants dropped out due to group issues such as feeling overwhelmed or reporting that the group did not meet their needs. Of the 236 who completed the programme, 202 (86%) provided time 2 data, and 93 (39%) provided follow-up data. Those who provided data at all three time points were not significantly different at time 1 to those who provided data for times 1 and 2 only.

Changes in psychological variables over time

A significant main effect of time was found for all variables (Table 2). Post-hoc analysis revealed a consistent pattern: pre-intervention scores were significantly higher than both post-intervention scores and 12-month follow-up scores for all measures. There were no significant differences between post-intervention and 12-month follow-up scores. Of note, the effect sizes associated with the changes from pre- to post-intervention were quite large, ranging from 0.74 to 1.21 (see Table 3).

Moderators of treatment effects

Initial levels of depression moderated changes in all variables in the short term, such that those with the highest levels of depression reported less pre-treatment gains on the primary outcomes: SIAS (r = −0.19, p < 0.005), SPS (r = −0.17, p< 0.05), FNE-R (r = −0.22, p< 0.005), SSB (r = −0.25, p< 0.005), SCQ Freq (r = −0.19, p < 0.05), and SCQ Belief (r = −0.16, p< 0.05). No other significant moderating effects were found for the primary outcomes. Table 2. Changes in psychological variables over time.

| Pre

M (SD) |

Post

M (SD) |

12 month

M (SD) |

Effect Size

partial η2 |

|

| Social Interaction | 52.55 (12.76)a | 40.14 (17.69)b | 38.20 (15.65)b | .56 |

| Social Phobia | 39.08 (14.42)a | 26.59 (14.05)b | 23.64 (14.47)b | .62 |

| Fear Negative Evaluation | 104.01 (24.64)a | 77.05 (29.84)b | 71.79 (31.86)b | .62 |

| Social Safety Behaviours | 42.51 (8.50)a | 32.25 (9.94)b | 34.25 (10.68)b | .43 |

| Social Cognitions: Frequency | 3.25 (0.71)a | 2.43 (0.72)b | 2.36 (0.80)b | .54 |

| Social Cognitions: Belief | 55.92 (19.20)a | 35.36 (18.01)b | 34.91 (23.23)b | .56 |

| BAI Anxiety | 21.16 (10.95)a | 13.11 (8.04)b | 11.40(8.33)b | .41 |

| BDI Depression | 20.33 (10.20)a | 10.33 (9.49)b | 10.94 (9.61)b | .55 |

Note: Different superscript = significant difference between means, p< .001 Clinical significance of changes scores

Table 3 reveals a high rate of clinically significant changes for both general anxiety and depression, with over half of the participants so classified. For example, 59% were classified in moderate to severe range on the BAI at time 1, with the rate significantly falling to 32% (χ2 = 53.15, p< 0.001) at time 2 and 24% (χ2 = 30.63, p< 0.001) at time 3. A similar pattern emerged for depression: moderate to severe depression deceased significantly from 57% at time 1 to 18% at time 2 (χ2 = 63.92, p< 0.001), and 15% at time 3 (χ2 = 34.57, p< 0.001). Between 40% and 50% of participants made clinically significant changes on the FNE-R and SCQ. For the SSB, SIAS and SPS approximately one third made clinically significant changes. Table 3. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for changes and rates of clinically significant changes (CSC) in variables over time

| Pre – post | Pre- 12 months | |||

| d | CSC % | d | CSC % | |

| Social Interaction | 0.97 | 30 | 1.12 | 33 |

| Social Phobia | 0.87 | 28 | 1.07 | 37 |

| Fear Negative Evaluation | 1.10 | 42 | 1.31 | 51 |

| Social Safety Behaviours | 1.21 | 30 | 0.97 | 33 |

| Social Cognitions: Frequency | 1.15 | 45 | 1.25 | 48 |

| Social Cognitions: Belief | 1.07 | 39 | 1.09 | 46 |

| BAI Anxiety | 0.74 | 50 | 0.89 | 54 |

| BDI Depression | 0.98 | 60 | 0.92 | 54 |

Participant satisfaction

Participants were generally very satisfied with the programme. For example, one participant noted the group experience as a ‘life-changing opportunity’ while another offered the comment that ‘just the fact that there is eight other people in the room who understand and share your fears and thoughts and don’t judge you, is a comforting experience’. However a number of disadvantages to a group format were noted; these included the potential for the group to be overwhelming, that it was too easy to hide, it was difficult to establish a pace suitable to everyone, inflexibility of group time schedule, and having to share the available time.

Discussion

The present findings strongly suggest that CBGT based on Clark & Wells’ (1995) model is effective in a general clinical setting. Moreover, the range of effect sizes reported and rates of clinically significant change compare favourably with previous literature (e.g. Strangier et al. 2003; McEvoy, 2007; Mörtberg et al. 2007). Of note, the specific anxiety disorder measures were more sensitive to change than the general mood measures. Furthermore, the largest changes (Cohen’s d > 1) over treatment were found in relation to specific aspects of social anxiety, namely social safety behaviours, social cognitions, and fear of negative evaluations. Moreover, gains were found over a wide range of psychometrically robust measures that assessed core features of Clark & Wells’ (1995) model of social anxiety; the findings support the proposition that the model can be successfully incorporated into group treatment settings with robust outcomes. The study also supports research (e.g. Gaston et al. 2006; McEvoy, 2007) demonstrating that a treatment model that was originally found successful in well-controlled research conditions can be successfully replicated and is effective in real-life clinical settings. The 6% dropout rate from the programme, which compares favourably with the dropout rates reported in other real-life settings (e.g. 18% reported by McEvoy, 2007), suggests that its format was acceptable to the majority of participants.

The finding that there was a significant reduction in depression severity is also promising. Furthermore, in line with Scholing & Emmelkamp (1999), depression was found to moderate the effectiveness of the intervention in the short term: those who scored high on depression showed less treatment gain. Although such effects were generally small, they support Chambless et al.’s (1997) recommendation of concurrent treatment of social phobia and depression for the more depressed clients. In the present group participants with mild to moderate depression responded well to treatment that focused exclusively on social anxiety; consequently such clients need not be excluded from CBGT participation.

Recent draft NICE guidelines for the treatment of social anxiety do not recommend group-based intervention. While the guidelines recognize that it could be successful in terms of outcomes, it contends that it is difficult to recruit socially anxious users, and is less cost-effective than individual CBT. For example, studies note that close to half of those with social anxiety who are scheduled for treatment either fail to commence or to complete treatment (Coles et al. 2002). Issakidis & Andrews (2004) reported a pretreatment attrition rate of approximately one-third. Furthermore, those who have social impairments are less likely to remain engaged in follow-up appointments in mental health services (Killaspy et al. 2000). Such research suggests that services have significant potential to enhance service uptake and retention among this population. Advertisement of a community-based CBGT through local GP practices, media campaigns combined with a dedicated websites/social media platforms may represent a means to attract referrrals in contexts where uptake is poor. If such approaches were sucessful, CBGT could be an efficient means to meet the increased demands placed on under-resourced services.

However, the present authors’ experience is that recruitment to the CBGT programme is not problematic. Our programme has a waiting list of 100–120 individuals at any one time; the majority of the applicants are self-referring. In this context CBGT helps address the high level of service demand. In addition, as noted recently, group therapy has unique therapeutic ingredients, and contrary to NICE guidelines there may be a value in considering group treatment as a viable option (Bjornsson et al. 2011).

While the authors of the NICE guidelines utilized sophisticated economic modelling to determine cost issues, it evaluated group intervention based on 30 h, two therapists and six clients (10 h per service user) (NICE 2012, table 20, p. 172). The present group (35 h, two therapists, nine clients) works out at 7.8 h per service user. Individual cognitive therapy based on Clark & Wells’ model is equivalent to 21 h per service user. The optimal model of CBGT remains to be determined; for example, shorter group sessions may prove equally effective. Furthermore, formal economic analyses of the cost-effectiveness of different treatment modalities requires empirical examination.

Treatment implications

CBGT was associated with good clinical outcomes and a high level of client acceptability (high completion rates). Although treatment gains were maintained for at least 12 months, the 12-month follow-up data are based on less than half of the original treatment group. Such a sample may be biased in terms of their current functioning.

The CBGT approach also provides an opportunity to shepherd group processes. Participants noted that membership of the group helped reduce their sense of isolation and fostered solidarity (group cohesiveness). It may help normalize experiences and provide a ready-made social format in which to take risks and break old patterns; furthermore, accurate and honest feedback, encouragement and support by fellow participants can have a more powerful impact on members than that coming from health professionals. In the present group, participants readily commented on these benefits of group participation. They also commented on the style of facilitation that worked best for them – firm but supportive. The use of humour was also highlighted as an ‘essential’ ingredient. It is possible that these factors may in fact facilitate attendance and the teaching of cognitive strategies and exposure exercises. Participant feedback indicated high levels of satisfaction with the programme. Taube-Schiff et al. (2007) found that increases in group cohesive rating over the course of the treatment significantly predicted post-treatment social phobia scores. However, the disadvantages of group-based approaches (e.g. being overwhelmed) noted by respondents must be acknowledged and represent fundamental challenges in providing group therapy sessions.

Limitations

The lack of a control group undermines casual inference regarding treatment effectiveness. The use of a waiting-list control group in future studies would be beneficial. Second, all data were self-reported and future research could examine if similar effects are found using clinician rating scales. Although the use of self-report scales is common in routine clinical practice, such measures may be subject to biased responding (Sato & Kawahara, 2011). Furthermore, while participants were requested not to alter any medication intake or attend alternative treatments during the programme this was not strictly monitored and thus may have influenced client outcome. The majority of participants were self-referred and may therefore represent a less avoidant and more motivated subset; indeed the very low dropout rate is consistent with high levels of engagement with the intervention. Furthermore, those completing all three time points may represent a biased sample; although the response rate is in keeping with rates reported elsewhere in the literature the findings from the current sample may not generalize to the wider SAD population. The reasons for dropping out of the CBGT programme were not systematically recorded; although the reasons noted included a mixture of external life events and issues related to the CBGT programme, future research should routinely collect data on dropouts to inform service delivery.

Despite the practical limitations inherent in clinical practice research we believe that research conducted in naturalistic clinical settings provides useful guidance in bridging the often wide gap between efficacy research and the effectiveness of interventions in clinical services.

Conclusion

Given the high completion rate, a CBGT intervention is acceptable to participants. The strong effect sizes, rates of clinically significant change and the 12-month maintenance of benefits across a wide range of measures testify to the effectiveness of CBGT for social anxiety.

Recommended follow-up reading

Clark, DM, Wells, A (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment (ed. R. G. Heimberg and M. R. Liebowitz ), pp. 69–93. New York: Guilford Press.

McEvoy, PM (2007). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural group therapy for social phobia in a community clinic: a benchmarking study. Behaviour Research and Therapy 45, 3030–3040.

Rodebaugh, TL, Holaway, RM, Heimberg, RG (2004). The treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review 24, 883–908.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., and Garbin, R.A. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory. Twenty five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77-100.

Beck, A.T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., and Steer, R.A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893-897.

Bjornsson, A.S., Bidwell, L.C., Brosse, A.L., Carey, G., Hauser, M., Mackiewicz Seghete, K.L., Schulz-Heik, R.J., Weatherley, D., Erwin, B.A., and Craighead, W.E. (2011).Cognitive-behavioral group therapy versus group psychotherapy for social anxiety disorder among college students: a randomized controlled trial. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 1034-42

Brown, E. J., Turovsky, J., Heimberg, R. G., Juster, H. R., Brown, T. A., and Barlow, D. H. (1997). Validation of the social interaction anxiety scale and the social phobia scale across the anxiety disorders. Psychological Assessment, 9, 21-27.

Chambless, D. L., and Hope, D. A. (1996). Cognitive approaches to the psychopathology and treatment of social phobia. In P. M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Frontiers of cognitive therapy. New York, Guilford.

Chambless, D.L., Tran, G.Q., and Glass, C.R. (1997). Predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 11, 221-240.

Clark, D. M., and Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg and M. R. Liebowitz (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–93). New York: Guilford.

Clark, D.M., Butler, G., Fennell, M., Hackman, A., McManus, T., and Wells, A. (1995) The Social Behaviours Questionnaire and The Social Attitudes Questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript. Oxford University.

Coles, M.E., Turk, C.L., Jindra, L., and Heimberg, R.G. (2002). The path from initial inquiry to initiation of treatment for social anxiety disorder in an anxiety disorders specialty clinic. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 457, 1 – 13

deWit, D.J., Ogborne, A., Offord, D.R., and MacDonald, K. (1999). Antecedentsof the risk of recovery from DSM-III-R social phobia. Psychological Medicine, 29, 569–582.

Evans, C., Margison, F., and Barkham, M. (1998). The contribution of reliable and clinically significant change methods to evidence-based mental health. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 1, 70-72.

Ehlers, A., and Clark, D. M. (1998). The Fear of Negative Evaluation Questionnaire- Revised. Unpublished manuscript. Oxford University

Faytout, M., Tignol, J. Swendsen, J., Grabot, D., B. Aouizerate, B., and Lépine, J.P. (2007). Social phobia, fear of negative evaluation and harm avoidance. European Psychiatry, 22, 75-79.

Feske, U., and Chambless, D. L. (1995). Cognitive-behavioural versus exposure only treatment for social phobia: a metaanalysis. Behavior Therapy, 26, 695–720.

Fedoroff, I. C., and Taylor, S. (2001). Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 21, 311–324

Gaston, J.E., Abbott, M.J., Rapee, R.M., and Neary, S. (2006). Do empirically supported treatments generalise to private practice? A benchmark study of a cognitive-behavioural group treatment program for social phobia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 33-48.

Gould, R. A., Buckminster, S., Pollack, M. H., Otto, M. W., and Yap, L. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment for social phobia: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 4, 291–306.

Heimberg, R. G., Mueller, G. P., Holt, C. S., Hope, D. A., and Liebowitz, M. R. (1992). Assessment of anxiety in social interaction and being observed by others: The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Behavior Therapy, 23, 53-73.

Heimberg, R. G., Juster, H. R., and Hope, D. A., and Mattia, J. I. (1995). Cognitive behavioral group treatment for social phobia: Description, case presentation and empirical support. In M. B.Stein. (Ed.), Social phobia: Clinical and research perspectives(pp. 293–321). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Issakidis, C., and Andrews, G. (2004). Pretreatment attrition and dropout in an outpatient clinic for anxiety disorders.ActaPsychiatricaScandinavica, 109, 426–433

Jacobson, N.S. and Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19.

Kessler, R.C., McGonagle, K.A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C.B., Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., Wittchen, H-U., and Kendler, K.S. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51, 8-19.

Killaspy, H., Banerjee,S., King, M., and Lloyd,M. (2000). Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 160-165

McEvoy, P. M. (2007). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural group therapy for social phobia in a community clinic: A benchmarking study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 3030-40.

Mattick, R. P., and Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of socialphobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 455- 470.

Mörtberg, E., Clark, D. M., Sundin, Ö. and Åberg Wistedt, A. (2007). Intensive group cognitive treatment and individual cognitive therapy vs. treatment as usual in social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 115, 142–154.

NICE. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment. [NICE Clinical Guideline X) Draft for consultation. London: Available online atwww.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12950/61875/61875.pdf [Clinical guideline X]; 2012.

Oei, T.P.S., and Boschen, M.J. (2009). Clinical effectiveness of a group treatment for anxiety disorders: A benchmarking study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 950-957.

Richards, D.A. and Borglin, G. (2011). Implementation of Psychological Therapies for Anxiety and Depression in Routine Practice: Two Year Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133, 51-60

Rodebaugh, T. L. Holaway, R. M., and Heimberg R. G. (2004). The treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review,24, 883–908.

Sato, H, and Kawahara, J. (2011). Selective bias in retrospective self-reports of negative mood states. Anxiety Stress Coping, 24, 359-67.

Scholing, A. and Emmelkamp, P.M.G. (1999). Prediction of treatment outcome in social phobia: a cross-validation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 659-670.

Steketee, G. S., and Chambless, D. L. (1992). Methodological issues in the prediction of treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology Review, 12, 387-400.

Stangier, U., Heidenreich, T., Peitz, M., Lauterbach, W., and Clark, D.M. (2003). Cognitive therapy for social phobia: individual versus group treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy 41, 991–1007

Taube- Schiff, M., Suvak, M. K., Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., and McCabe, R.E. (2007). Group cohesion in cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 687–698.

Taylor, S. (1996). Meta-Analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatments for social phobia. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 27, 1–9.

Wells, A., Stopa, L., and Clark, D.M. (1993). The Social Cognitions Questionnaire. Unpublished Manuscript, Oxford University

CBT Group Treatment

The programme, which largely adopts a cognitive

behavioural model, is conducted over fourteen weeks.

If you wish to apply for a place on our Social Anxiety

Programme please read and follow the instructions in

the section ‘Process of applying for a place in our

Social Anxiety Programme.’

We Need Your Help!

Donations

We’re 100% non-profit and rely on the good will of people like you to enable us to continue to provide this invaluable treatment for so many people throughout Ireland.

100% of your donation goes towards helping people with Social Anxiety Disorder.

Latest News & Events

With the support of people like you, we’ve been able to help thousands of people throughout Ireland. Keep up to date with all things SAI via our blog with weekly updates, news, service updates and helpful information.